There are differences between the way houses are often built in Australia and the way they’re built in Canada. I’m not a builder but even I can see some of these differences. In many areas of Canada, a house will be built with a basement as the foundation. However, at least where I live in Australia, most houses are built on top of a flat concrete slab. But either way they have a solid foundation. You wouldn’t dream of building without one.

The Protestant Reformation was about getting the church back on a solid foundation. For the Protestant Reformers there was but one such foundation: God’s Word. From that we receive one of the key tenets of the Reformation: sola Scriptura. The Bible alone is our foundation. As the Belgic Confession states in article 7, “Since it is forbidden to add to or take away anything from the Word of God (Deut. 12:32), it is evident that the doctrine thereof is most perfect and complete in all respects.”

It’s quite easy to maintain this principle merely in an abstract fashion. However, sola Scriptura is meant to be lived. The Bible is not only the foundation for theology in the academic sense, it’s also meant to be the foundation for the life of the church and the life of every Christian. Let’s briefly explore two ways of living “sola Scripturally.”

Worship

A moment ago I mentioned the Belgic Confession and what it says about the sufficiency of Scripture. Interestingly, earlier in article 7, the Confession connects the sufficiency of Scripture to public worship: “The whole manner of worship which God requires of us is written in it at length.” It’s in the Belgic Confession because it was a contentious issue in the Reformation. The Roman Catholic Church didn’t maintain the sufficiency of Scripture and that was reflected in how it approached public worship. Many practices were introduced into the worship of God which had no warrant from God in his Word.

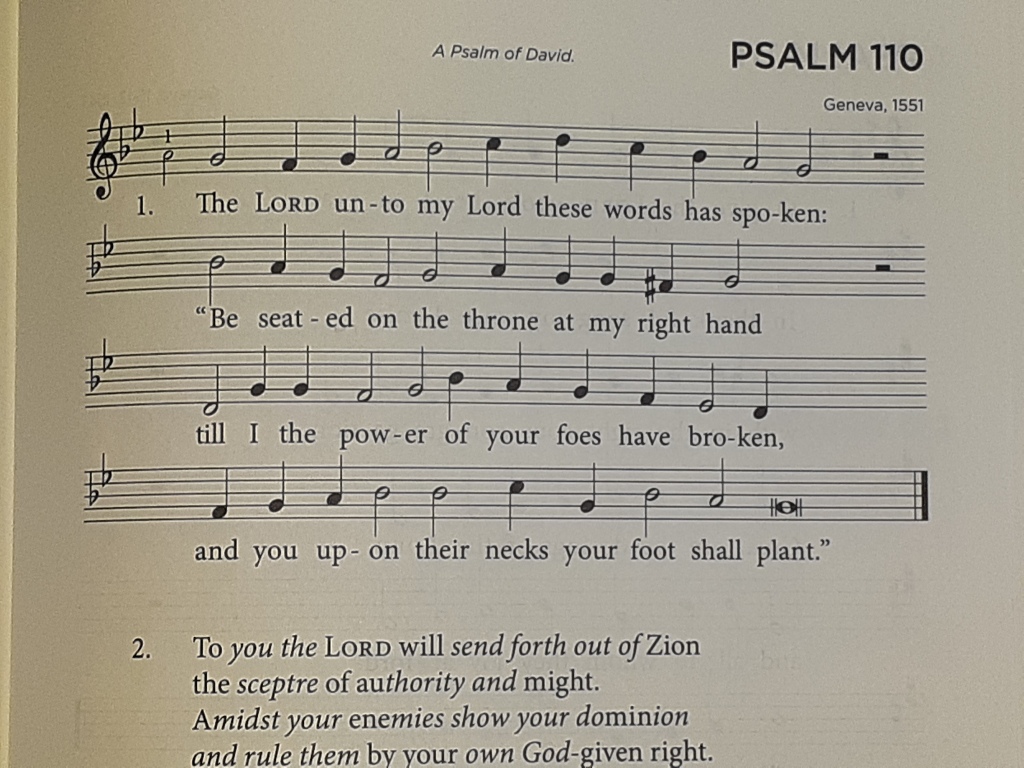

Contrary to that, the Reformers insisted that God’s Word alone can determine the elements of our public worship. This eventually came to be known as the Regulative Principle of Worship. As the Heidelberg Catechism expresses it in QA 96, “We are not…to worship him [God] in any other manner than he has commanded in his Word.” Scripture alone is the foundation for Reformed worship.

So one of the ways we live “sola Scripturally” is that we aim to worship God only in his ways. For example, the church can never substitute anything for the preaching of God’s Word. Scripture commands (2 Tim. 4:2) that we must have preaching – authoritative proclamation by a man ordained for that task. And Scripture also commands that it be the preaching only of God’s Word. It can’t be human opinions, nor can it be “preaching” based on what God is supposedly revealing in a TV show or movie. Perhaps that seems obvious, but sadly, it’s not so obvious to many churches not upholding the Regulative Principle of Worship.

Apologetics

Over the course of my 20-plus year ministry so far, there’s been a surge of interest in learning how to defend and promote the Christian faith. Back in my seminary training, apologetics wasn’t even taught and there was a level of suspicion attached to it. Today that’s changed and it’s all for the better.

However, the Reformed approach to apologetics (pioneered by Cornelius Van Til) is still very much the minority opinion, especially in your vanilla Christian bookstore. Why this matters has to do with foundations. Non-Reformed apologetics builds on something other than the Scriptures. Sometimes it’s human rationality and our ability to evaluate arguments or evidence; at other times it might be our sense perception. Regardless of the details, we’re looking at an approach that’s building on a foundation of sand.

What distinguishes Reformed apologetics is a commitment to sola Scriptura. This commitment isn’t just lip service. We actually go to what God says to find out how to defend and promote what God says. The Bible holds the content of our apologetics, but it also determines our method.

1 Peter 3:15 is often referred to as the “Magna Carta” of apologetics. Here the Holy Spirit tells us that we’re always to be prepared to offer a reasoned defence of our faith. However, the first part of the verse is sometimes overlooked: “…but in your hearts honour Christ the Lord as holy.” One of the best ways we can do that in apologetics is by building on the foundation Christ gives in his Word. We need an apologetical method which is determined by Scripture alone. Reformed apologetics supplies that method.

Conclusion

The word “Reformed” is often reckoned as short-hand for “Re-formed according to the Bible.” While true enough, we could improve it by adding one little word: “alone.” To be Reformed is to be constantly going back to the Bible alone. The reason we do that is because it’s the only sure foundation for our lives as individuals and collectively as the people of God. It’s been said that you have to stand somewhere in order to get anywhere. If the place you’re standing is sinking sand, you’re going nowhere. But if you’re on solid rock, you’ve got the traction you need. Only the Word of God provides that.